A tribute to Bill Tutte and the other unsung heroes of Bletchley Park

98 years ago today, a hero was born. A man whose genius cracked a seemingly indecipherable Nazi code - providing the Allies with invaluable information and helping to shorten World War II by at least two years.

If you asked others who he was, I daresay the majority of people would come up with the name of Alan Turing.

They would, of course, be completely wrong.

|

| Professor W. T. (Bill) Tutte |

This is W. T. Tutte (also known simply as 'Bill Tutte'). He is a man whom we all should be eternally grateful to. The sad thing is, though, that he and many others who worked at Bletchley Park have been almost forgotten - due to the posthumous accolades heaped on Alan Turing in more recent years.

Now, don't misunderstand me. There is no doubt that Alan Turing was an extremely gifted mathematician and his work on German Naval Enigma should be recognised. However, there has been a tendency to overpraise his contribution - to the extent that some people seem to think that Turing alone was responsible for cracking the Nazis' coded messages.

Nothing could be further from the truth. At its peak, Bletchley Park employed no fewer than 9,000 people, who worked on a variety of ciphers. While Turing's work on German Naval Enigma was instrumental in helping the Allies gain advantages by ascertaining the positions of the German U-Boots in several battles, it was by no means the most difficult code to break.

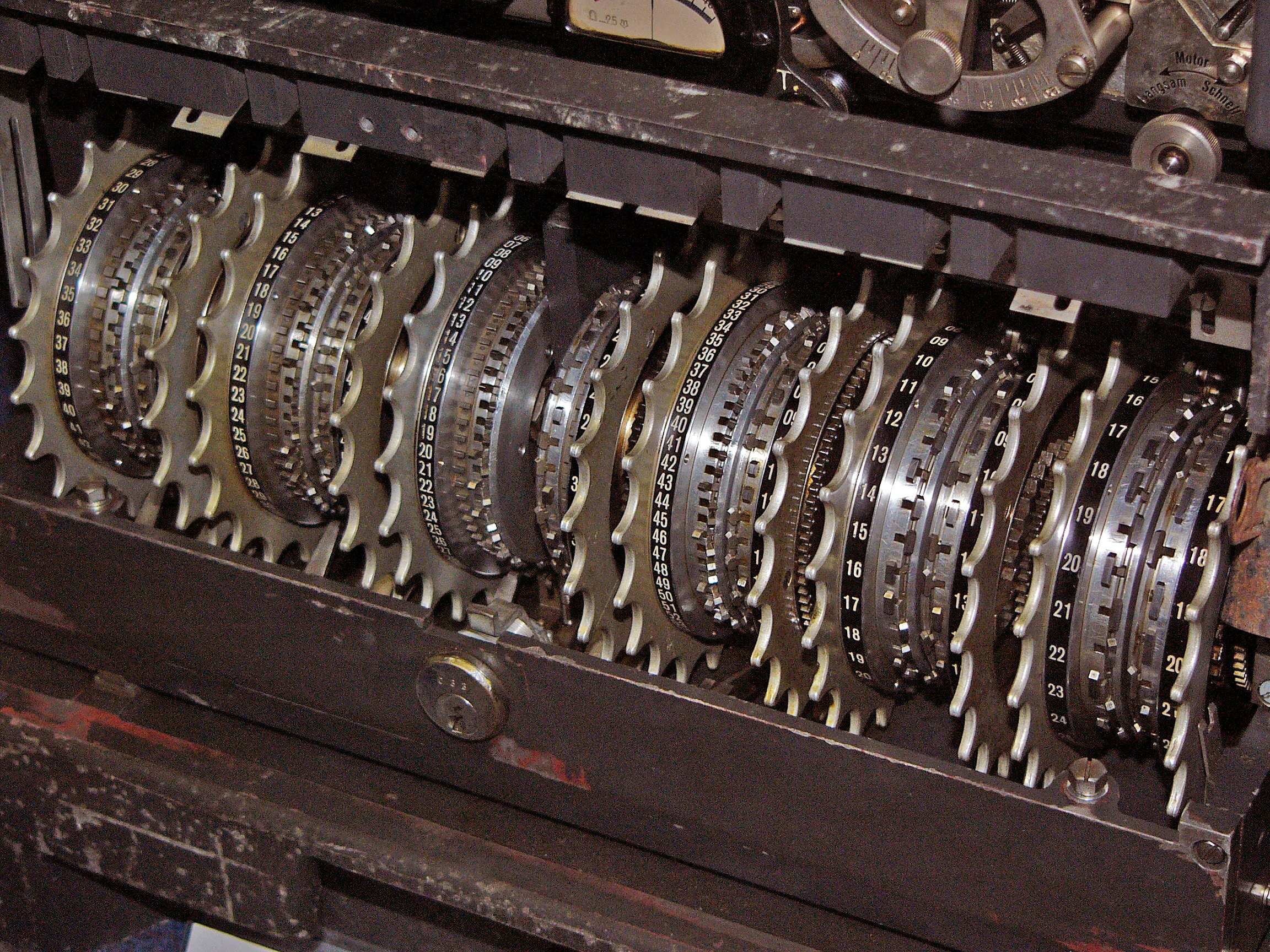

That honour belonged to the Lorenz code. This was the code which was used by the German High Command, and Hitler himself. The complexities of Lorenz itself can be found in greater detail here. Suffice to say that while the basic Enigma code was encrypted via four wheels (producing 15 million million different combinations), the Lorenz cipher had a total of twelve (resulting in 1.6 billion million possibilities). Moreover, while the codebreakers knew what an Enigma machine looked like (thanks to the work of the Poles prior to the war), nobody had any idea of what the Lorenz machine entailed. The fact that someone managed to crack it at all was referred to as "one of the greatest intellectual feats of World War II".

|

| A Lorenz cipher machine |

And who was the person who managed this feat? He was born William Thomas Tutte in Newmarket, Suffolk on 14 May 1917. He seems to have had a fairly inauspicious start to life as the son of a gardener, but soon displayed the academic prowess that took him on to a scholarship at Trinity College, Cambridge and a First Class Honours degree in Chemistry.

When the Second World War broke out, the Government Code and Cypher school began to search for mathematicians and codebreakers to work on breaking top-secret Nazi communications. Tutte's Cambridge tutor, Patrick Duff, recommended him for a position, and Tutte was interviewed and sent for training in London - before arriving at Bletchley Park in around 1940.

After apparently being rejected by Turing for the Enigma team, Tutte joined the Research Section. Initially, he worked on the Hagelin cipher, but in summer 1941 was transferred to work on the Lorenz code (nicknamed 'Tunny' by the British).

At around the same time, a breakthrough with Lorenz was made by the brilliant linguist and cryptanalyst Brigadier John Tiltman. On 31 August 1941, a German officer sent an encrypted message twice. The officer made the fatal (and forbidden) mistake of using exactly the same settings for both messages. Not only did he do that, but the second message contained slight differences from the first in the form of abbreviations. Just from this, Tiltman managed to decipher, character by character, what the message said.

The only problem was that British Intelligence still did not know how the Lorenz machine worked precisely - as Tiltman had only cracked one possible sequence for the code. At a loss, the task was then handed over to Bill Tutte. And Tutte, unbelievably enough, succeeded in deducing - via his own intuition and mathematical formulas - how many spokes the first wheel must have and the number of wheels needed to produce the entire Lorenz code and its myriad combinations.

After apparently being rejected by Turing for the Enigma team, Tutte joined the Research Section. Initially, he worked on the Hagelin cipher, but in summer 1941 was transferred to work on the Lorenz code (nicknamed 'Tunny' by the British).

At around the same time, a breakthrough with Lorenz was made by the brilliant linguist and cryptanalyst Brigadier John Tiltman. On 31 August 1941, a German officer sent an encrypted message twice. The officer made the fatal (and forbidden) mistake of using exactly the same settings for both messages. Not only did he do that, but the second message contained slight differences from the first in the form of abbreviations. Just from this, Tiltman managed to decipher, character by character, what the message said.

|

| Brigadier John Tiltman |

The only problem was that British Intelligence still did not know how the Lorenz machine worked precisely - as Tiltman had only cracked one possible sequence for the code. At a loss, the task was then handed over to Bill Tutte. And Tutte, unbelievably enough, succeeded in deducing - via his own intuition and mathematical formulas - how many spokes the first wheel must have and the number of wheels needed to produce the entire Lorenz code and its myriad combinations.

There is one other person whom I must not neglect to mention here. His name was Mr Tommy Flowers, an engineer and employee of the Post Office. Although Tutte had succeeded in cracking the Lorenz code, it would still take several days of slow, laborious work to decrypt messages. As time was of the essence, the Allies desperately needed a way to speed up this process.

|

| Mr Tommy Flowers |

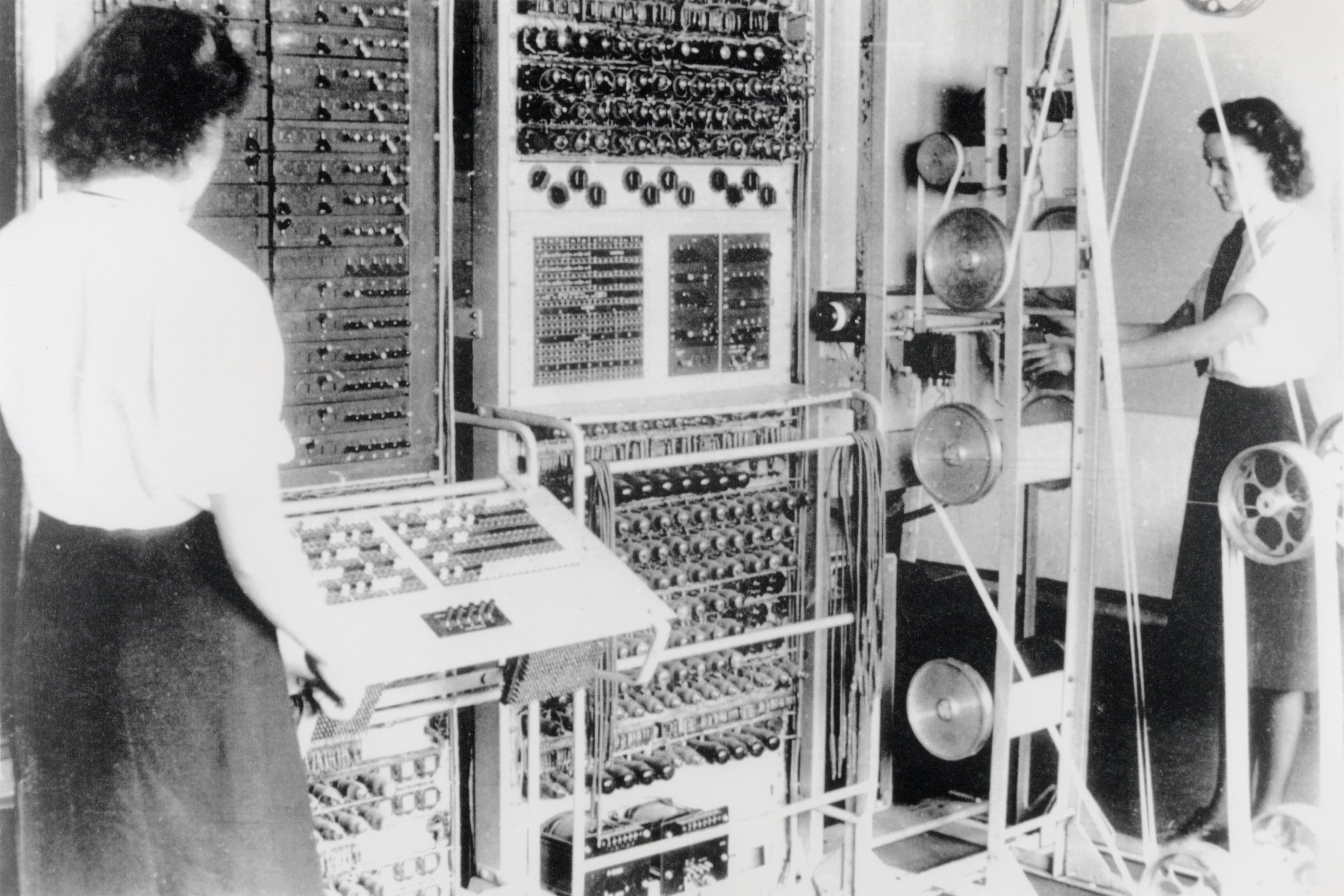

Alan Turing's friend and mentor, Max Newman had been working on a counting machine (dubbed the "Heath Robinson"), which they hoped would crack the Lorenz messages quicker. Unfortunately, the Heath Robinson proved to be ineffective due to the slowness of its electro-mechanical parts and the difficulty of synchronising two paper tapes. It was Flowers who provided the much-needed solution, by inventing Colossus - the world's first programmable computer.

This in itself was an extraordinary achievement. You have to bear in mind that if someone wants to design a new computer nowadays, they already have a wealth of knowledge and previous models which they can build upon. In fact, the microprocessor in the modern computer (itself designed by someone else and the product of 60 years' Research & Development) executes 99.99% of its instructions from pre-existing subroutines. Remember that MS Windows contains 37 million man years of work in its coding - a lot of which is "third order" (i.e. written by a machine).

In contrast, when Tommy Flowers designed Colossus, he started with absolutely nothing except (valve based) analogue electronics. He had to come up with it all, and a lot of what he produced is still used in modern computers. Indeed, the reference in the preceding paragraph to 60 years of R&D began with Colossus itself.

|

| A Colossus Mark 2 computer |

Colossus allowed the Allies to decipher messages sent via Lorenz cipher in a matter of hours instead of days and provided them with invaluable information on what the Germans were planning. Most notably, this played a central role in the success of the D-Day landings in 1944.

Aftermath

Sadly, the secrecy that surrounded the work at Bletchley Park also had its price. After the war, Churchill ordered all the equipment to be dismantled and the files on everything that had carried out to be sealed. Thus, for several decades, the world never knew of the vital and pioneering work carried out by the codebreakers.

Of all of them, Turing's life probably makes the best "story" - due to his subsequent conviction for gross indecency and his strange, untimely death at the age of just 41. Hollywood, especially, has seized upon this - as evidenced by the success of the recent motion picture, "The Imitation Game."

|

| 'The Imitation Game' - a popular, Oscar-winning, but inaccurate biopic of Turing |

Alas, as alluded to above, such films seem to serve only to promote Turing's role at Bletchley Park ahead of everyone else's - even though the contributions of many of the other codebreakers were equal to (and occasionally outstripped) his.

Tommy Flowers, in particular, was reportedly unhappy that many now erroneously credit Turing with the invention of the world's first computer. Unfortunately, Flowers was never truly able to reap the rewards and accolades for his creation. The British government paid him £1,000 which did not even cover the costs of his own money which he had put into building Colossus. Later, he tried to apply for a loan to build a similar machine, only to be turned down because the bank did not believe it would work. Frustratingly, Flowers was unable to tell them about his earlier model because he was strictly bound by the Official Secrets Act.

Brigadier John Tiltman fared slightly better. He continued his distinguished career as a cryptanalyst at both GCHQ and the National Security Agency for several decades after the war - becoming one of the few to make the transition from the manual ciphers of the early 20th Century to the sophisticated machine systems of later decades. He was posthumously inducted into the "NSA Hall of Honor" in 2004 (the first non-US citizen to be recognised in such a manner).

As for Bill Tutte, he completed his Mathematics doctorate in 1948 and subsequently moved to Canada. He enjoyed a respected position as a professor at various universities, gaining recognition in the fields of graph and matroid theory. He passed away in 2002 at the age of 84. Twelve years later, his home town of Newmarket unveiled a memorial to him - pictures of which can be seen here. It's just a shame that more people are not aware of his story.

Comments

Post a Comment